Please Attend

Part of my interest in historical invitation cards or exhibition flyers relates to how they index time. There is something essential that is preserved and tangible in the invitation. It reflects a moment and can depict a variety of facts: the what, where and how of an art event, the particular surface and printing technology used to transmit the message,

and very often, the traces of the hands it passed through from the designer to the addressee. In this regard, I often think of a little invitation from 1974 announcing a talk by

Dan Graham that I found a few years ago in the ephemera collection that I work with at the MoMA Library in New York City. It states all of the basic facts of the event, but

then also, the receiver of the card had scrawled the word TODAY in large print on the face of the card. This additional text makes more emphatic this aspect of iterating a time relation, of announcing an event. Written by hand and underlined, the word «TODAY,» probably a note from the receiver to herself, adds another voice to the card. This declaration of the present tense can be seen as mundane or humorous, but also makes the card a more curious object. It makes clear that the functionality of the invitation, its usefulness

in the present, also becomes part of the aura that we can find emanating from these pieces of printed matter as they pass into archives and help construct a record of events relating to historical exhibitions and the biographies of curators, artists and designers. From an art historical perspective, the information from posters and cards often provides a connection between artists, designers and shared activities and art spaces. They can portray legible narratives and material evidence for temporary events and installations. Certainly, other archival sources like performance photographs and first-hand accounts can also reveal rich context for the art historical record. But, in these little paper scraps, we have a primary resource for thinking through networks of artists, galleries and institutions and also the cross-pollination between the visual arts, graphic design and other arts,

like dance, theater, poetry and literature. A cumulative view of these materials becomes a chart, using this specific format to characterize certain practices in contemporary art.

One major characteristic that can be gleaned from a broad view of contemporary art ephemera is the degree that artists and designers play with the established graphic con-

ventions of the format. Just as artists and designers have used other printed formats in strange and unexpected ways, the format and structure of invitation cards or exhibition posters have been appropriated and played with to various ends. A great example of this scenario of turning the format on its head is a card created by a collective called Gorgona from Zagreb. In 1962, members of Gorgona, a loosely organized group of artists, designers and historians in Zagreb, sent out an invitation for a gallery exhibition called Modern Style. The invitation simply stated in rather formal type, «IZVOLITE PRISUSTVOVATI,» which can be translated in English as, «PLEASE ATTEND.» There were no other discerning markings or information that would lead you anywhere—just that one was invited, generally. Thinking of anti-art activities that were bubbling up around the globe

at this time, like Nouveau Réalisme in Europe, or downtown New York visual arts, sound and performance experiments, the Gorgona invite could be equated as an anti-invite. As with other elements of Gorgona’s practice, like their eponymous magazine, which they literally called an «anti-magazine», the invite symbolically empties out or intervenes with the conventional encounter with the object and creates another open-ended relation. The details are abandoned and one could experience this as pure aporia and / or an affirmed condition of being absolutely welcome. One can imagine a friend or colleague receiving the Gorgona invite at the time, turning it over, inspecting the other side for more information and maybe simply discarding it as a strange and useless anomaly. Maybe, another person would have laughed and recognized somehow this as the work of a friend.

A more general issue of the Gorgona invitation as it relates to artists’ invitations was the ambiguity of these little papers, of their existence as introductions to works and events and as «works» themselves. The Gorgona invite is a piece of early concept art as well as an actual, though somewhat useless, announcement for other works that were presented in Zagreb at a Gallery G in 1962. A dynamic element of these materials is their ability to be several things at once. They could be works, and/or operative elements of a larger works, extensive art historical data about an event, and also strange interventions within the act of inviting or announcing.

The invitation card decidedly presents itself as an index of time, an index of an event that occurred or will occur. Another aspect of its importance in contemporary art is more a spatial relation. The scale and substance of a little card or flyer are often considered proportionate to an attitude of ephemerality adopted in conceptual art practices. For artists and designers that have a style or tone that relates to minimal or temporary interventions in an art space or other social space, the medium of artists’ ephemera presents a form that is in step with this kind of attitude.

We can see how a conceptual artist like Robert Barry, who had also utilized gas or atmosphere as a medium, found the space of the invitation conducive for his work. Barry notably conducted two «works» through gallery invitations. For example, in Closed Gallery, the announcement communicates that for the run of the exhibition the gallery will be closed. This was staged three times through the mail in 1969, through an announcement by the Los Angeles gallery, Eugenia Butler, and through announcements by Art & Project and Galleria Sperone. Or we can think of the Croatian artist Goran Trbuljak whose early gallery exhibitions in the 1970s comprised just the poster that advertised the exhibition. For exhibition from 1971, a single poster filled the gallery of the Student Center in Zagreb and contained a portrait of Trbuljak and read, «I do not wish to present anything new

or original.» An aspect of this kind of conceptual announcement, or in this case, a kind of declaration, is in its transmission, its movement across space. It is easily dispersed and decidedly veers away from the monumental and into the everyday or also, the imaginary. When the site of an artwork is intentionally elusive or if there is an operation

that must happen first to experience the work in a particular setting, the invitation can be an operative portal through which to enter a work. We can think of Daniel Buren’s urban interventions in the 60s and 70s with his painted vertical stripes. An essential part of these works was the invitations that relayed a telephone number to be called «in order

to see» and which had the heading: YOU ARE INVITED TO READ THIS AS A GUIDE TO WHAT CAN BE SEEN.

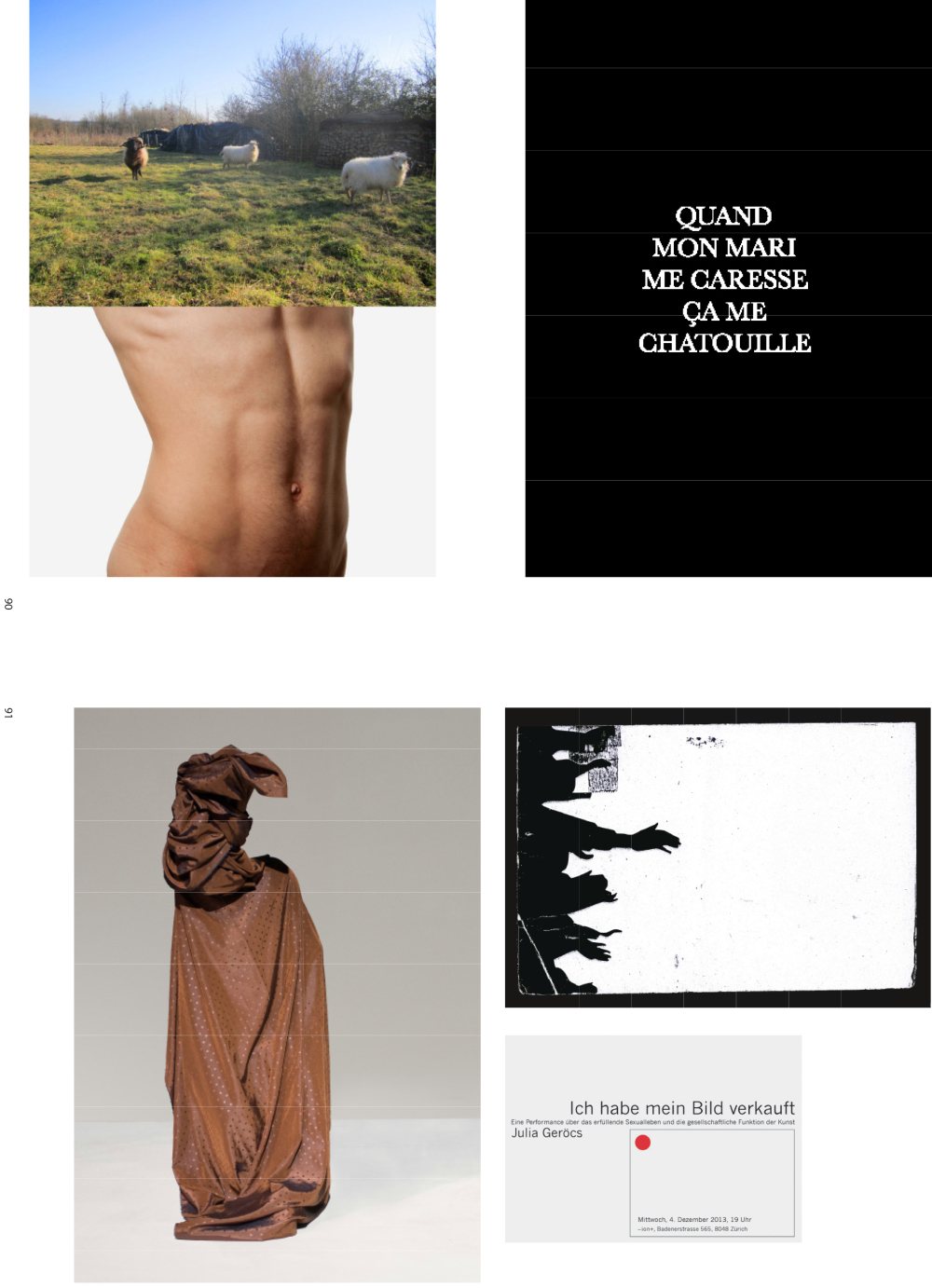

Aside from being subtle partners in the history of conceptual art works, we also know that posters, flyers and cards can make noise. The recent history of these materials also illus-

trates the ways that they can disrupt space, how they can be brash and noisy, irreverent and funny. Many of these kinds of printed matter could be considered punk; accessing cheap printing tools to scrawl subversive, surreal or goofy messages across town. There is often a production ethos that relies on what is easily available to draft, print and distribute these materials. This is part of the history of DIY print culture, which also corresponds directly to the history of artists-run gallery spaces and other underground venues for exhibition, music and performance of the past 40 years from around the globe. The directness of this kind of flyer design and the cheap production values are often a necessity, but also, consistent with the work being announced. They give us a view into the types of print processes that are accessible to broke young artists and designers and the spirit of the events staged in experimental art spaces. In our contemporary moment, this sensibility has not necessarily faded, despite wholly new digital contexts for communication and distribution of images. I witness a surprising uptick in this activity—perhaps as a stubborn reaction to our digital milieu by artists and designers who still print, still create this kind of ephemera. There is some strange opening that is created by print’s outmodedness. Perhaps it is too early to say exactly what that opening is or what it means, but the material evi-dence is clear from my vantage point. The printed matter of the art and design world flourishes in the present as a decidedly relevant and very open space for graphic experiments and the transmission of ideas.

David Senior is Bibliographer at The Museum of Modern Art Library. He is responsible for collection development as well as the selection of materials for the artists’ books collection. He also regularly organizes exhibitions of MoMA library material. Recent exhibitions have included «Scenes from Zagreb: Artists’ Publications of the New Art Practice» (2011), «Millennium Magazines» (2012), an exhibition of contemporary artists’ magazines and «Please Come to the Show» (2013), a two-part exhibition of special invitation cards and event flyers from the Library’s ephemera collections. His writing has recently appeared in Frieze, Bulletins of the Serving Library, A Prior and C Magazine.